Inertia and Non-Synchronous Generation

|

|

Mark Henry

|

The Bulk Power System (BPS) takes advantage of Newton’s First Law of Motion —objects in motion tend to stay in motion — to maintain stability. The kinetic energy inherent with the mass of spinning synchronous generators at fossil-fueled, hydro, and nuclear power plants provides what is called system inertia. It acts somewhat like a shock absorber to dampen the effects of disturbances, slowing down the resulting rate of change in grid frequency, and allowing time for controls and operator actions to return conditions to the normal range.

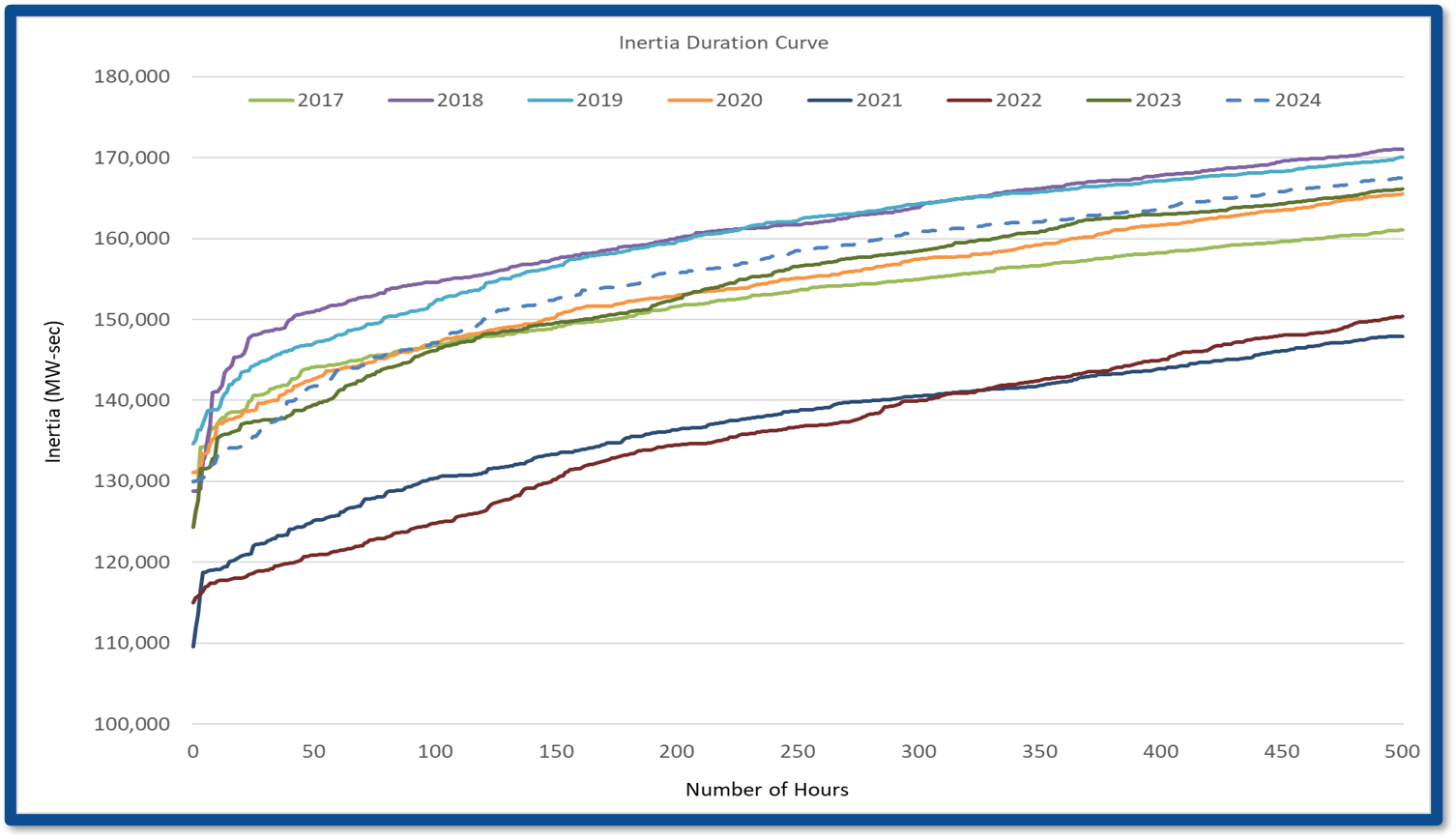

Non-synchronous generation such as wind and solar power do not supply inertia. The chart below shows the Texas Interconnection’s inertia levels over the past eight years. Periods with higher levels of renewable generation and low demand produce the lowest levels of inertia (left side of curves). Too low a level of inertia might lead to an inability to arrest a frequency decline following credible disturbances. The Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) has determined a critical minimum level of inertia that operators track in real-time. While today’s margins are above the critical level necessary to provide secure operations, continued rapid integration of renewables could lead to inadequate inertia when synchronous generation is not on-line.

Today’s battery energy storage systems (BESSs) do not provide inertia but are capable of using their stored energy in a similar manner, so-called “synthetic” inertia that can supplement that of synchronous generators. This synthetic inertia, along with fast frequency response from batteries (and perhaps enhanced demand flexibility) will help provide stability for the future grid if fewer synchronous generators are in-service.